Postmortem: Indigo Prophecy What Went Wrong

1: The Story - The Bad

Generally speaking, the scenario and characterization worked particularly well but a few glitches in the writing prevented the scenario from reaching the level of quality I was aiming for.

Here are some of them in no particular order:

- one bad guy per story is enough: the Oracle was the real enemy in Indigo Prophecy and I think his characterization was quite good. The AI that comes into play at the end of the game only adds confusion to the plot.

- you can make people believe anything in a scenario, but only once per story. In the case of Indigo Prophecy, the story of Lucas, guilty of a murder he never really committed because controlled by the Oracle, was THE unreasonable proposition in my scenario, which the players accepted without difficulty. The series of new developments at the end, although built into the first scene (the crow representing the AI is a leitmotif throughout the game) constituted a series of added propositions that went beyond what the players/spectators could reasonably accept.

- I made the mistake of not devoting enough time to the last hour of the game. I was convinced (and rightly so) that the first hour of the game would be decisive for hooking the player, but I naively thought that one hour from the end the player's opinion would be made. I therefore devoted most of my time to the rest of the game in order to make it as perfect as possible.

This was obviously a mistake. I was forgetting that what leaves a lasting impression on the player is often the end, and that a bad ending can change his perception of the whole game.

It won't happen again…

2: Graphics: "Atmospheric but not Stellar" (as they said…)

The graphical quality of Indigo Prophecy was given an uneven reception by the critics. I think there are three reasons for this:

- Indigo Prophecy was developed simultaneously on three platforms, PS2, Xbox and PC. PS2 had been defined as the lead version and no efforts were spared for this console. The last months of development were devoted to graphically improving the PC and Xbox versions, but too few specific features were developed for these platforms to make these versions competitive with the best games on the market.

- the second reason was a deliberate choice to work on the graphics in terms of atmosphere rather than in terms of a technical demo. In order to create a grim atmosphere by working on the colorimetry and the grain of the image we deliberately avoided easy lens flare and other such env map effects that invade most games. The result probably lacked eye candy.

- the last reason relates to a misevaluation of needs in terms of tools. The graphics team did top quality work but the tools that would have facilitated the graphical production appeared much too late in the production or were not suited to the job. The heaviness of the technology always has direct repercussions for the graphical quality of the game: when a graphic artist spends more time trying to view his work than improving it, the result is a loss of quality.

The burden of having to develop an internal technology on three platforms proved to be too much to afford the artists the comfort they needed.

On our upcoming productions we have devoted a significant effort to developing the graphics and animation tools entirely in pre-production. More specifically, we have greatly extended our WYSIWYG philosophy enabling direct visualization on console in all tools.

3: Action Sequences - Almost A Good Idea...

The action sequences are a good example of a good idea that never came to maturity during the development of the game unlike, say, MPAR and MultiView. Reviews were globally good for this part of the game, which was designed from the very beginning more as a spectacular breath of fresh air in the narration than as a veritable game play challenge. I am personally dissatisfied with the result.

The initial concept was to avoid having repetitive action sequences like most games, where the player accomplishes the same actions (shooting, fighting, driving).

The narrative structure imposed a great variety of actions, animation and situations in order to preserve the cinematographic side of the experience and there was no question of imposing shoot sequences every ten minutes at the risk of totally destroying the narration.

The other important point in the project specifications was that the camera should be free to provide top quality directing (so no views from behind). Finally, there was no question of providing specific interfaces for each new action scene. We therefore had to imagine a generic interface that was equally suited to a chase scene, a game of basketball or ice-skating.

The result was the PAR system (japanese designer experimented something similar with his Quick Time Events in SHENMUE).

The final idea of assigning controls to the analog sticks and bonding them to the movements of the character on the screen came quite late in the development, too late for the appropriate tools to be developed. The implementation was thus very largely blind, and the tuning particularly long and delicate.

In addition, we failed to find an ideal visual representation for the symbols on the screen. We tested a large quantity of positions, sizes, shapes and colors and finally opted for peripheral player vision. It was an interesting option but not entirely convincing, the interface being graphically too invasive. If the player does not use peripheral vision, the eye moves from the symbols to the scene and the interface masks the scene.

A better implementation would have been possible if we had had complete WYSIWYG tools earlier in development.

4: Insufficient Overall Vision for the Technology

The Indigo Prophecy technology is not really spectacular. It was primarily intended to serve the experience of the game and fluidity. Most of its features were designed to improve the game experience.

For example, the game is not burdened by any loading in the course of scenes thanks to an "intelligent" streaming system that enabled the game to offer a particularly large quantity of action per square meter.

The scripting tool we used to assemble the game enabled us to construct extremely complex scenes with a great number of possible variations and a great variety of mechanisms. The MultiView and Multi-Character scenes were veritable technical challenges.

In spite of many positive points, the game suffered globally from an insufficient overall vision for the technology. This placed a considerable burden on the development and demanded not inconsiderable extra efforts that the team could otherwise have avoided.

The first mistake occurred when changing platforms. Developing a PC game is very different from a console game, particularly in terms of memory management, loads and saves. We considerably underestimated the switch from PC to console and failed to identify the difficulties correctly (we quickly focus on the frame rate, whereas the memory and loading issues are considerably more problematic).

The second mistake was an insufficient analysis of the game design. It seemed to be very simple (playing animation in scripts with conditions) whereas it finally proved to require great underlying complexity. Synchronously managing several scripts playing simultaneously in several windows but capable of interacting with each other, as in the Hotel scene, is just one example of the type of cases that had to be managed.

We also underestimated the needs of a game that uses few recurrent mechanics.

The other classic error we committed was trying to develop generic tools with a view to possible future productions rather than tools dedicated to the experience of the game we wanted to create. The initial scripting tool was supposed to enable us to script both an FPS and a tennis game. The reality quickly proved to be different from the theory.

A generic tool enables management of a great variety of cases… but none of them very effectively. The prospect of reusing a tool as is for future productions is usually a pipe dream that costs time and money in the short term with no guarantee of profitability in the long term.

In Indigo Prophecy we realized this early enough to be able to correct the error. We adapted the tool, making it less generic but more effective for the type of game we were developing. With a scripting tool that was better suited to the game, we considerably simplified the scripting and accelerated the development.

The reality of development in the years ahead is that engines will no longer constitute a veritable barrier, and there is a strong chance that all teams will very quickly have access to the same features.

The real technological stakes of Next Gen development are in the tools.

5: Difficulties of Developing an Original Concept

The major difficulty in Indigo Prophecy was being able convince before, during and after the development, publishers, the team, the marketing, the journalists and finally the gamers.

Convincing a Publisher

The difficulties inherent in an original project begin even before it goes into development with the incredibly difficult task of convincing a publisher.

Indigo Prophecy was no exception to this rule.

I often say that a truly original project cannot be signed by a publisher except if based on a misunderstanding, because if the publisher really understood what he was signing, he would never sign it.

The initial presentation of Indigo Prophecy was capable of terrifying even the most foolhardy of publishers (and these are few on the ground…). The challenge of the project was to create an experience in which the player would control the main protagonists of a story in which his choices would modify the course of events. No gun, no car, no action, no puzzle…

The first publishers I spoke with took me at best for a harmless dreamer, at worst for a madman. The publisher's first reaction when evaluating a new project is to look at the sales figures for games in the same category. In my case, he either considered that the game was a new genre, therefore having no comparable reference, or else that it belonged in the category of adventure games, an economically minor genre. Clearly not a good omen for Indigo Prophecy…

The other difficulty I ran up against was trying to explain the experience that Indigo Prophecy was going to be. Even today I still find it difficult if not impossible to explain what the game is like to someone who hasn't played it. The dialog inevitably ends with the person looking at me with a puzzled expression accompanied by a polite smile.

Because it really is impossible to explain Indigo Prophecy (you can make the test yourself…).

In an action game you can explain how to shoot, what weapons are used, who the enemies are, and everyone immediately understands the type of experience it is going to be.

With Indigo Prophecy, no one can see right away how the player can enjoy playing with only a story and choices.

Explaining the concept of an original game with no real prior references is a major difficulty that must not be underestimated. I had to deploy considerable efforts before I finally managed to generate enough excitement to sign for the project, after spending more than a year discussing it with the publisher.

Convincing During Production

Developing an original project also constitutes a mass of difficulties at all levels of production. Apart from the initial difficulty of convincing the publisher to take the risk of trying something new, you then have to convince them that the project is making progress.

Lots of publishers need to be reassured by the game play early on in the development and demand vertical slices (a full playable game level complete with all the features). This method is perfectly suited to shooters or car games where we can in fact produce a complete level and have a good idea of the final game play because all that remains is to duplicate the game play by changing sets.

The immense difficulty of the Indigo Prophecy concept was that a large part of the fun came from involvement in the story and emotion, which were both difficult to illustrate from a single isolated scene.

Because Indigo Prophecy didn't really use repetitive mechanics, playing an isolated scene demonstrated nothing except how that scene worked, without any indication of the context nor of the feeling the game would finally produce.

Moreover, it was difficult to perceive the typology of a game based on emotion as long as everything had not been set up, animation, dialogs, facial, lighting, rendering and most of all music. It was a bit like watching film rushes and trying to imagine the final result.

To optimize production, I had chosen to structure the development horizontally rather than vertically and produce all the animation, all the sets, all the characters, while simultaneously beginning to assemble. The result took time before it became visible but when it did, the whole game appeared "as if by magic" from one day to the next.

Production models should be adapted to the specific nature of the project, rather than just copying the established recipes. All games should not be produced like action games. Some creativity also has to be put in new methodologies to develop these games, more in line with their true nature and in respect with the publisher's constraints.

Convincing the Team

Managing the development team constitutes the other difficulty involved in producing an original project. When working on a FPS, the team has a very clear idea of what it is doing from the very first day of development. It has outside references that enable it to judge the quality of the game.

With an original project, this does not apply. The team had to have enormous faith in order to be able to produce Indigo Prophecy. Some of the team members even admitted to me that they had not really understood what Indigo Prophecy was all about until after the game was released and they heard their friends talking about it.

Anyone who has already directed a project knows how essential it is to have the complete confidence of the development team. If the team has reservations or no longer believes in the project, that project will fail.

For Indigo Prophecy, I made a point of never showing my doubts (which were nevertheless numerous and sometimes difficult to overcome all through the development) and made special efforts to share my vision of the project with the team.

Here again, the special nature of Indigo Prophecy and the fact that it was difficult to understand the experience of the game before everything was fitted together, did not make life any easier for me, but the team stuck with me all the way and I was genuinely touched by their confidence. I would like to take advantage of this occasion to express my gratitude to them.

Conclusion

Indigo Prophecy was really an extraordinary experience both professionally and in human terms. I learned an enormous amount from it and it profoundly changed my vision of interactivity. I won't make video games the same way before and after Indigo Prophecy, and I think it also deeply changed the vision of most of the people in the team.

And although the game may not be perfect, I hope that the passion and enthusiasm that the team and I invested in it will nonetheless make it a game that is both different and sincere.

In my personal development it constitutes an important stage toward making video games not just simple toys but a veritable form of expression. I hope it has given other more talented people the desire to explore interactive narration and the formidable capacity of this new medium to create emotion.

Publisher: Atari

Developer: Quantic Dream

Platforms: PlayStation 2, PC, Xbox

Number of full time developers: Around 80

Length of Development: Two Years

Release Date: September, 2005

Autor: David Cage

Source: Gamasutra

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

INDIGO PROPHECY: Developer's Diary

CONCLUSION

The release of Indigo Prophecy marks the end of a personal and collective adventure during which I believe we all learnt a lot about our work and ourselves. Now that the game is released, it will start its own life, some people will hopefully love it, others will probably not see the passion and ambition we put in it and just see it like one more videogame.

As a game designer, I believe that Indigo Prophecy brings some interesting answers that will hopefully bear fruits at Quantic Dream and elsewhere. I hope that other creative talents more gifted than we are will see the potential of what we discovered and will want to tell their own stories.

Indigo Prophecy fulfills many of my expectations as a gamer, and hopefully those of many others desperately waiting for a different kind of game with more depth, maturity and meaning. I hope they will give the opportunity to this strange game to seduce them.

If the strange story of Lucas Kane and Carla Valenti emotionally reaches one person and leaves a little trace in his memory, I will be more than satisfied...

Author: David Cage

Source: 1UP

- About Indigo Prophecy

- THE CONCEPT

- THE CONCEPT

- Some Thoughts About Games

- Interactive Storytelling, or the Holy Grail

- Interactive Storytelling, or the Holy Grail

- THE GAMEPLAY

- Game Design

- The Pen to Tell the Story: The Interface

- Game Mechanics

- Multiview

- Action Sequences

- The Pen to Tell the Story: The Interface

- THE STORY

- The Scenario

- Episodic Content

- Characters

- Episodic Content

- THE TECHNOLOGY

- Production

- Rendering

- Cameras

- IAM

- MOCAP

- Music

- Rendering

- CONCLUSION

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

INDIGO PROPHECY: Developer's Diary

THE TECHNOLOGY

Production

The full production of Indigo Prophecy took nearly 80 people about two years to develop, plus we used around 60 actors and stuntmen for the animation and voice work. The game was simultaneously developed on three platforms (PS2/Xbox/PC) using proprietary technologies, engines and tools. The game features about 12 hours of optical motion capture animation, and about three hours of speech translated into seven different languages.

Rendering

For Indigo Prophecy, we wanted to pay specific attention to rendering. We did not want to follow what you typically see in games with clean rendering, lens flares everywhere, and shiny environment and bump mapping all over the place. We were more interested in the quality of the final image in general, like in movies. We developed a technology based on post-rendering filters that allow you to change the key color of a scene to give it a special atmosphere. Most of the scenes are slightly tainted in blue to give them this cold key color feel. Each image is treated with a second layer of high dynamic range effects, a rendering technique that increases the intensity of the light sources and slightly blurs everything on the screen. A third layer was applied with a light grainy noise too, in a similar fashion to what you see in Silent Hill. The result is nothing that you could describe as "eye-candy" at the first glance, but when you play the game, it really gives a unique atmosphere to the experience. Like the interface, it is something the player will forget after the first few minutes, but it greatly supports the ambiance.

Cameras

In a game like Indigo Prophecy, the camera work is important. We wanted to have a technology that would give us as much freedom for direction as we would have if we were producing a real movie. I also wanted to give the player the possibility to participate to a certain extend to the direction without it becoming a burden for him. In short, he should be able to see what he wants to see, when he wants to see it.

The idea of having several cameras positioned on "the set" and all tracking the player was inspired by television broadcast. For live shows on television, all cameras track the action, and the director decides which one he wants to use. We used a very similar system with four cameras at four points in each room. Each camera is positioned by us, can be static or moving on a trail, and trails can communicate together, allowing the camera to move from one to the other seamlessly. With the left and right triggers on the controller, the player can switch between these four cameras all the time, and this guarantees that he will always have a view showing him what he wants to see. We just added a subjective view to the whole system for close ups to complete the system. Of course, we had to face the usual navigation issues when you don't have a camera in the back of your character, requiring that the player gets used to it, but the gain was really significant.

The idea of having several cameras positioned on "the set" and all tracking the player was inspired by television broadcast. For live shows on television, all cameras track the action, and the director decides which one he wants to use. We used a very similar system with four cameras at four points in each room. Each camera is positioned by us, can be static or moving on a trail, and trails can communicate together, allowing the camera to move from one to the other seamlessly. With the left and right triggers on the controller, the player can switch between these four cameras all the time, and this guarantees that he will always have a view showing him what he wants to see. We just added a subjective view to the whole system for close ups to complete the system. Of course, we had to face the usual navigation issues when you don't have a camera in the back of your character, requiring that the player gets used to it, but the gain was really significant.For the more complex scenes requiring a high quality of directing, we have developed a tool that we call "M3" (Movie Maker Module) that is a kind of directing bench like Adobe Premiere, only in real time 3D. Very complex cut scenes like the murder in the opening sequence were done with this tool. It probably gave me more freedom than having a real camera, because with a virtual camera, you can cross the walls, go wherever you want without constraints, and change the lens at will. The tool also integrates filters and special effects as well as sounds. All events are represented as blocks that can be moved and copied. Cameras and trails are directly placed in the real time 3D window with the possibility to place them while the animations play or are paused. For other scenes, we synchronized several movies that were played in Multiview in different windows.

M3 is really a dream for any director. The only limit is your imagination and you can try as long as you want and see immediately the result. I often thought that real directors would kill to have something like that rather than their heavy cameras.

IAM

IAM (Intelligent Adventure Manager) is the scripting tool we used for the game. It is a proprietary technology we created for our previous game Omikron. The philosophy behind it is really simple; allow game designers themselves to assemble the game in real time. The entire tool is based on a simple language that anyone can learn without any programming skills, and it offers a graphic interface to enter instructions and triggers. IAM made complex scenes like the one in the diner possible with many possibilities and paths that would have probably been a complete nightmare without this tool. The tool also manages the conversation trees too, something that was a real gift when building a game offering three hours of interactive dialogue in seven different languages!

MOCAP

In terms of motion capture use, Indigo Prophecy is probably one of the most demanding games ever made. It was clear that this would be the case when I started working on the project, and this is why we decided to have a motion capture set at our studio. Indigo Prophecy could not have been done without that.

The sessions took us about three months, which is about the same as it would take to make a real movie. We recreated the 3D space where the action was taking place in the game with props and accessories to give some reference points to the actors. Directing actors for motion capture is a very specific task. The main difficulty is to help them understand the situation and act without having a real set or costume to react to. I tried to pay as much attention as possible to the quality of the acting. Another difficulty was the fact that several people intervene in the creation of one character. Three or four different actors worked on the motion capture for Lucas (depending on the required skills, acting or stunts), someone else provided the voice, and another person was in charge of the facial animation. Several months sometimes separated these elements, which meant that keeping an eye on consistency as it passed through each artist was extremely important.

Facial animation was made using a unique technique we developed based on a puppeteer and motion capture gloves. Each facial animation (phonemes for lips synching, eye browse, smile, anger, irony, etc.) is assigned to different fingers. The puppeteer triggers them in real time like a real puppet to animate the face. We also added the possibility to animate the faces in our movie maker and by script to make sure that faces would show emotions all the time, and not only in cut scenes.

Music

For the soundtrack, I absolutely wanted to work with a movie composer that would bring a different quality of emotion to the game. I knew a lot of video game composers who would have done some "John Williams" stuff, with a big orchestra, but I wanted exactly the opposite, something sensible, emotional, the kind of soundtrack that we don't often hear in games.

Angelo Badalamenti was on my list almost from the beginning. I discovered his work in Twin Peaks a while ago and I was totally amazed by the wonderful atmosphere he added to the series. As a big fan of David Lynch, I followed his work in all his movies as well as his collaboration with French director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Working with Angelo quickly became an obligation in my mind. He was the best person to translate into a music score the fate of Lucas Kane.

I had a good experience working with gifted musicians, after my collaboration with David Bowie on Omikron. Both have been incredibly easy to work with.

My only recommendation to Angelo was to forget that he was working on a video game, and think about his work exactly like if it was a real movie. I sent him the full scenario, a synopsis, the bible, visuals, storyboards, movies of the game, the full game of course and some boring long documents explaining my hopes for the music. Angelo was extremely receptive and open-minded. When he made me hear the first theme he wrote for Lucas during the opening sequence, it was obvious it was the right one. It had all the emotion I was looking for, this dark, epic, human feeling I was desperate to hear. He then worked on themes for all of the characters. The soundtrack was recorded with a full orchestra in Canada under the direction of Normand Corbeil who did a wonderful job.

NEXT >>

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

INDIGO PROPHECY: Developer's Diary

THE STORY

The Scenario

It is always difficult to know exactly where inspiration comes from where you write a story. I remember that the first idea for Indigo Prophecy came while watching Brian De Palma's Snake Eye. The story was about a murder seen from different perspectives through the flashbacks of the different characters. I felt that this idea was a great gameplay mechanic and I started working on the idea of a murder in a public place. Most of my influences came almost exclusively from movies. I felt that a lot of things that were seen as "established" should be reconsidered for Indigo Prophecy. Mechanics, ramping, interface, all these things had to be different in order to create the kind of experience I had in mind.

I remember pitching my game to a journalist and hearing his response, "storytelling? That's not fun!" My answer was simple, "define fun." Our discussion fell short... The usual definition of the "fun factor" takes us back to the notion of "killing and destruction," but I had nothing like that in my concept... I knew I would have to face this kind of resistance and prove that fun can be created in different ways.

Back to my influences, I was inspired by movies like David Fincher's Seven for the way the intimate backgrounds of the characters are closely linked to the main story, Fight Club for the way voice over work was used, as well as David Lynch's Dune. Voice over work helped a lot in Indigo Prophecy, both as a useful narrative device and as a strong gameplay component. Adrian Lyne's Jacob's Ladder (a true masterpiece) inspired me when it came to the deformed reality attacking Lucas, and Alan Parker's Angel Heart was a great source for tackling a character with no other choice than to face his destiny.

Back to my influences, I was inspired by movies like David Fincher's Seven for the way the intimate backgrounds of the characters are closely linked to the main story, Fight Club for the way voice over work was used, as well as David Lynch's Dune. Voice over work helped a lot in Indigo Prophecy, both as a useful narrative device and as a strong gameplay component. Adrian Lyne's Jacob's Ladder (a true masterpiece) inspired me when it came to the deformed reality attacking Lucas, and Alan Parker's Angel Heart was a great source for tackling a character with no other choice than to face his destiny.The idea that we don't really have any true choice in our daily lives was a very interesting concept for me, especially when presented in a media based solely on choices. In our lives we believe that we are free, but we usually only do what is expected from us. We can do virtually anything, but we just do what sounds reasonable. The allegory was perfect with the narrative experience I was trying to create. I wanted to make the player believe that he is entirely free, but of course, he just does what I was expecting him to do. The hero himself states that very clearly in the opening sequence by saying that he is "just a pawn living his pawn's life." Of course, this is a little bit esoteric and very few people will pay attention, but I guess it gives a special flavor to the whole experience.

Episodic Content

Initially, Indigo Prophecy was supposed to be sold as an episodic game. I started working on the plot and the first episodes based on the TV series format, with an ongoing story, recurring characters and cliffhangers at the end of each of the 12 episodes. I wrote a full bible for the world and all of the characters with the idea to create a reference in order to share the writing between several writers. I also developed a significant number of side stories that would run in parallel, generally related to the lives of the main characters.

This is how I came with the more intimate scenes in the game; Carla at her apartment, Tyler dealing with his private issues with his girlfriend, Lucas with his ex-girlfriend, etc. I wrote all of these scenes where we see the main characters at home in their private lives dealing with their personal affairs in order to generate some side stories that I could develop throughout the episodes. When the format was abandoned, I did not have the heart to cut them entirely, so I left bits in here and there. Without this history, I guess I would have never thought about writing these scenes this way. I really think that they significantly contribute to make Indigo Prophecy the experience it is today.

Characters

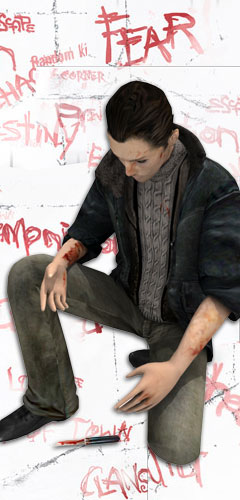

Splitting the focus of the game between the main characters was an important task. Because the game was based on the idea of switching between different characters, all of them had to present some kind of focal point, although it was obvious from the start that there would be only two real heroes to the story, Lucas and Carla. Their roles were defined quite early in the process. Lucas would be the cursed hero, accused of a murder he did not really commit, and the victim of visions trying to kill him while he searches for the truth, while Carla would be the professional, cold investigator, only believing in reality. He would be on the supernatural side; she would be on the reality. Although one is the murderer and the other the cop, they both have the same goal; namely to discover what happened the night of the murder.

The player alternates between the different characters, collecting clues from both sides, and being the only one to get the full picture. As we see in Hitchcock movies, the audience always knows more than the characters.

Tyler Miles, Carla's teammate, was an interesting character for us to develop. I tried to characterize him as much as possible, by making him a kind of Shaft-style character, stuck in the 70's. He is also the only character with any funny scenes in a story that is generally quite dark.

I decided at the beginning of the project that the opening sequence would have to be very striking. I wanted the player to be immediately thrown into the story and have him empathize with the main character. Making Lucas a murderer was a difficult decision to make. I was convinced that the player would empathize with a character accused of a murder he did not really commit though. He would easily identify with Lucas and would share his fear. Many people, especially from marketing, feared that the player would be reluctant to help someone he did actually see killing someone. They were wrong. When we started testing the game, we quickly realized that people liked the idea of being a murderer not responsible for his actions.

From a narrative perspective, the guilt felt by Lucas was extremely interesting. Are we responsible for what we do even if its something we have no control over? Giving Lucas a brother who is also a priest was a convenient way to expose his struggle. Markus represents the law and morality, while Lucas is about ambiguity and fatalism. I guess this contrast reinforces the empathy the player feels for his character.

NEXT >>

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

INDIGO PROPHECY: Developer's Diary

THE GAMEPLAY

Game Design

Writing the full game design document took me about a year to complete. The final script is about 2000 pages and integrates absolutely everything; story, characters, gameplay, structure, branching dialogs, horrible sketches, maps and storyboards (I am terrible at drawing), instructions to remember for acting and directing, indications about music and sounds and much more. With the experience of another very complex game (Omikron), I have established some rules for my game designs in order to put all the possible information in there while keeping them clear (I hope). This document was the master document for the whole production. It was truly our "bible", the absolute reference for everything.

Very few changes happened during the development. The number of people involved and the mass of data produced would have made any change extremely time and resource consuming. This is why I usually pay a lot of attention to the game design document to avoid having to make changes on the fly. Trying to set the game design in stone at the beginning of development is generally a noble wish, but it is also important to leave some space for what is discovered during the process. Whatever efforts you make to try to plan the game on paper, you always have some surprises when it comes to the screen; some good, some bad.

Our first tests on the game brought both good and bad news. The good news was that the storytelling seemed to work well. After a couple of hours of play, a pleasant feeling of attachment to the characters appeared. They were real characters, consistent and with a personality. The player felt like he knew them, knew their tastes, how they would react, where they came from, a little bit like in a TV series. The pacing of the narrative was also working well, because as the player moved between the different playable characters, the different sets and situations, the story was always moving along. Unfortunately the pacing of the game itself appeared to be way too slow on all levels though. Moving across a room was really painfully slow, there were cut scenes every two steps, dialogs lasted hours, etc. In our anticipation of the balance between narrative and interactivity, we obviously gave too much importance to the narrative, which killed the fluidity of the experience. We made massive adjustments to the pacing of the game, speeding the navigation animations by 30 per cent, cutting all unnecessary cut scenes and speeding up the remaining ones. The game was suddenly totally transformed. We came from something that was slow and boring to a fast moving experience. The story finally found its own pacing.

Our first tests on the game brought both good and bad news. The good news was that the storytelling seemed to work well. After a couple of hours of play, a pleasant feeling of attachment to the characters appeared. They were real characters, consistent and with a personality. The player felt like he knew them, knew their tastes, how they would react, where they came from, a little bit like in a TV series. The pacing of the narrative was also working well, because as the player moved between the different playable characters, the different sets and situations, the story was always moving along. Unfortunately the pacing of the game itself appeared to be way too slow on all levels though. Moving across a room was really painfully slow, there were cut scenes every two steps, dialogs lasted hours, etc. In our anticipation of the balance between narrative and interactivity, we obviously gave too much importance to the narrative, which killed the fluidity of the experience. We made massive adjustments to the pacing of the game, speeding the navigation animations by 30 per cent, cutting all unnecessary cut scenes and speeding up the remaining ones. The game was suddenly totally transformed. We came from something that was slow and boring to a fast moving experience. The story finally found its own pacing.Time pressure also became a major element of the game play. I absolutely wanted the story to move along all the time, trigger events on its own and push the player forward. I did not want to let the player to slow the pacing of the narrative except in specific situation. In the diner at the beginning of the game, Lucas is under pressure because the cop may stand up at any time. In his apartment, he has the premonition of the cop arriving and has a limited time to decide what to do. I tried to take every single opportunity to make the world accelerate the story.

As I said, very few changes to the design happened during the development of Indigo Prophecy. The most significant one was probably the idea of the actions and choices modifying their mental health, making them feel good or bad about themselves and affecting their psychological state. To do this, we take physical actions into account, and also all the moral choices the player has to make in the story and the relationships he has with other characters. In the original script, everything was in place to make the player feel good or bad about his actions. In my mind, if the player decided to save a child by risking his own life, he would feel good about it. On the flipside, deciding to play it safe and let the kid die would make him feel bad. I thought that these feelings would happen in the player's mind and that they would be obvious. When I could play the entire game for the first time, I felt that this idea was a little too abstract for the player. He would clearly need a visual representation of his mental health to make it more tangible for him. This is how we decided to add the little mental gauge in the lower right corner of the screen. We also decided that the character's animations would depend on his level of mental health, making it even more obvious for the player. Then we realized that many other actions implemented in the game should affect this gauge and that we needed to add a consequence if the characters get totally depressed. We developed the full system in a couple of weeks, including the game over sequences. The tools were robust enough to allow such a significant change so late in the development.

The Pen to Tell the Story: The Interface

I felt comfortable with the solutions I had found so far for the storytelling part, but another important element was still missing to be able to tell a decent interactive story: the interface. Most video games use a list of actions limited to about 15 to 20 maximum. The reason for that is easy to understand: there are about 10 buttons on a game controller. It is difficult to have more actions than buttons. I really see the interface as the pen we give the player to write the story. The issue is that telling a good story with a hero only able to do 20 different actions is very difficult.

The idea of having contextual actions quickly appeared to me as being the right solution. I would have an infinite number of possible actions that I could use depending on the situation. The final missing piece in this puzzle was to make the player forget the interface. Often, the controller is just a remote control to move a bunch of pixels on screen. For Indigo Prophecy, it had to be a part of the experience, an extension of the player's physical body in the world of the game. I wanted him to touch objects, make the moves with his character, to feel how his character feels.

Inverse kinetics would have been an interesting solution to actually move the arm of the character in the world while doing the same move with the analog stick, but the results were too unpredictable. Also, I did not want to distract the player with the interface from his main focus; the story. The solution had to be simple and fluid, context sensitive and supporting immersion without distracting the player. It sounded to me like a very ambitious challenge.

Then I started working around the idea of momentum; the simple feeling of initiating the motion with the stick, making the move, and at the same time working within the boundary of the movement itself. I called this system MPAR for Motion Physical Action/Reaction (I love meaningless acronyms!)

Simple symbols at the top of the screen describe the movement the player has to perform in order to unfold the animation. He can really "play" it, decide to do it faster or slower with the analog stick, or even play it back and forth. No need to have more menus or icons, no need of "Examine/Combine/Take" anymore, the player just decides what he wants to interact with and makes the appropriate move.

With the Bending Stories writing technique and this new approach to interface with my contextual MPAR, I had the basic words of the narrative language of Indigo Prophecy.

I just still had a thousand major issues to solve before having the final script of the game.

Game Mechanics

Another interesting challenge was to solve the equation of game mechanics. Most games taken at their core are based simply on pressing the right buttons at the right time. The player progressively acquires the necessary skills to understand the best timing and order depending on the information given by the program. As the game progresses, timing becomes more and more tight. These games are based on repetitive patterns of actions triggered by patterns of controls.

If games are based on short and repetitive patterns, stories totally hate them. A story has an arc, and the range and diversity of the hero's actions to solve his issues are a significant part of storytelling. If videogames usually give the priority to physical actions, a major part of the story usually takes place in the mind of the character, where he has to face moral choices and dilemmas. Difficult to play that by just pressing buttons...

In short, my objective was to provide an experience that didn't rely on short control patterns, didn't need repetitive mechanics, and I wanted to provide the possibility for the player to make "non-physical" choices. Having no real mechanics in a game is a very interesting exercise. To me, there is no other way of creating a storytelling experience than to let the story generate its own mechanics. The story becomes a "puzzle maker" in 3D. It creates the context for choices and manages the consequences. There are of course some mechanics, but I tried to make them as invisible to the player as possible by integrating them directly into the context. For example, I often used time pressure in the scenes. In the opening scene, the player must hide a dead body in the restroom of a diner before someone comes in. This timer will be perceived by the player as a logical event in the context of the story, but at the same time it puts pressure on him by forcing him to think fast. It adds stress and tension to the scene while making the player "feel" like he really committed a murder.

Multiview

Multiview is another example of this blend of mechanics and storytelling. When I saw the TV series 24 for the first time, I was amazed by the potential of this feature. Not only did it have a wonderful visual appeal, but it was also a great gameplay feature. Instead of having a cut scene to show what was happening in another place at the same time and lose interactivity, Multiview would allow me to open another window in real time 3D and let the player continue to play while watching what's happening. For example, when Lucas leaves the diner in the first scene of the game, I can show the cop discovering the dead body in the restroom while still allowing the player to control the hero's actions.

Implementing Multiview has been an interesting technical challenge, to say the least. First of all, we had to make the decision of implementing this feature based on the idea of displaying up to four real-time 3D scenes in four different windows, at a time where the engine was not optimized at all. In fact, at this point it was only running at about eight frames per second with one window. It showed considerable faith in our technology to believe that we would be able to display those four views at 30 frames per second, which is what we eventually were able to do.

The other important consequence of Multiview was the necessity to have a multi-threaded script and the possibility of the need to synchronize threads. We needed to execute the main script in the player's window, but also to have other threads with up to four complex scripts running independently. We also needed to accommodate the possibility of hooking two threads together when they needed to be synchronized. Last but not least, memory constraints were massive. Four times the data from the same scene means four times the memory requirement. On PS2 especially, managing loading times and memory constraints has been really challenging.

For example, there is a complicated scene in the game where Lucas is hidden in a hotel; Carla and Tyler are in the corridor looking for the right room so they can arrest him, and Lucas' brother Markus is in his church with the villain trying to kill him. These three scenes are loaded and displayed in three windows at the same time, and the player can freely switch between these three characters. The entire scene takes place in real time and each character can influence other windows: Lucas can call his brother to warn him, Carla and Tyler can enter in Lucas' room, Markus can decide to answer the phone or be killed by the villain. Most people won't even realize the technical difficulty of these scenes, and this is why I think it works so well. Technology should be invisible and always allow the experience to be at the forefront.

Action Sequences

When I made the decision of going for this new action interface, I knew some people would love it, while others would hate it. My thinking was simple; I was looking for an interface that would allow me to have very spectacular action sequences, where each scene was different and each was presented with a strong sense of pacing and direction. I had to find a generic interface that would allow me to do car chases, ice-skating, basketball, dancing, fighting and anything else I could think of. I knew the result would be amazing-instead of always having the same repetitive shooting scene with the same 20 animations, I could have any type of action with spectacular animations and direction.

At the same time, I was thinking about what was really important in any action scene, namely timing and precision. I suspect that Yu Suzuki was thinking along similar lines when he was designing the Quick Time Events in Shenmue. This approach has become more and more popular in recent years, and it's been used very effectively recently in games like Resident Evil 4 and God of War. In Indigo Prophecy, I tried something slightly different based on the same concept. I wanted to keep the idea of physical immersion, a direct link between what the player is doing on his controller and the motion on screen, but I found that Shenmue's QTE were quite disconnected from the action. The decision to use the two analog sticks rather than the buttons seemed to be the right approach.

I also wanted to increase the amount of user input. I didn't want a Dragon's Lair style experience, but rather a kind of Dance Dance Revolution kind of feel. Making the character move should be a sort of dance. He has two arms and two legs, there are two analog sticks. It sounded like a good fit. The decision to put the two rings in the middle of the screen was an audacious one I think. It takes some time to get used to it, but it really works, and I think it increases the feeling of immersion. We did tons of tests with positioning, sizes, colors, but none of them worked as well as the one we implemented. We discovered that while the center of the eye was focused on the 2D symbols in the middle of the screen, the periphery of the eye tries to have a sense of what's going on in the background. In my mind, this is exactly what would happen if the player were in the situation for real; the center of his eyes would be focused on his next move while also trying to see what's going on around him. It requires some time for the eye to get used to the system, but when it works, it creates a kind of third dimension that significantly increases immersion.

NEXT >>

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

INDIGO PROPHECY: Developer's Diary

THE CONCEPT

Some Thoughts About Games

After the development of my previous game Omikron, I started asking why there aren't more people playing videogames. I can appreciate the same books, TV shows and movies as, let's say, my parents, but they definitely could not have the same appreciation that I have for videogames. Why is this?

I asked people of different ages, tastes, and backgrounds why they don't play video games to try and get to the bottom of this. The answers were always the same: "Videogames? They are for kids," I was told. "They are too complicated," some admitted. "I don't have time for that," or "I don't understand anything". The truth for many people is that they just aren't interested.

At the same time, I stumbled upon another group of people too: the "ex" gamers. These were people who played videogames when they were kids, but quit at some point to do more serious stuff. These people told me things like "I don't have time to play anymore," which I interpreted as "I'm not interested anymore."

All of these people could understand the entertainment value of literature, TV or cinema, but not the value of games.

These simple thoughts initiated the process that led me to design Indigo Prophecy. I tried to take one or two steps back to see video games through their eyes. As a pure geek and videogame addict since the Oric 1 home computer, it's been an interesting exercise.

I started to truly open my eyes at a conference I was participating in with a keynote speaker from a major publisher. The man brilliantly summarized his vision of videogames with his first sentence: "What do

I started to truly open my eyes at a conference I was participating in with a keynote speaker from a major publisher. The man brilliantly summarized his vision of videogames with his first sentence: "What dogamers really want to do in games? They want to destroy. We decided to give them what they want".

Was this really the publishers' vision of interactivity? Is "Destroy" the key word defining players' expectations? Are they really a herd of teenagers whispering, "REDRUM" like in Kubrick's movie "The Shining"?

If that was really the case, I probably had to reconsider what I wanted to do in life. At the same time, it would explain why so many people were not interested at all in videogames: most of them would have more expectations from a form of entertainment than just to shoot at zombies or destroy cars.

So I started to search in my gamer's memory for all the games I have played, trying to figure out if the word "Destroy" could define them all. The answer was "No" or to be more accurate, it was "No, but almost".

In fact, I realized that most games were based on the same five basic emotions: excitement, competition, fear, frustration, and pride.

In short, excitement is about the pleasure of displaying power by killing or destroying (like in any shooter game), competition is about showing that we are better than the others (like in sports games or any game with competitors), frustration is about failing and starting again, and pride is about getting unique items and customizing one's character.

These primitive emotions are based on two neurotransmitters, adrenaline and dopamine. Both are known for their physical effects on the body and in the case of dopamine, for its addicting power.

"Five emotions to rule them all," five primitive feelings to describe all games.

I would be lying if I said that I did not understand why some people could have no interest in videogames. I felt something similar myself to a certain extent. For a while, I had the feeling that games were just repeating themselves over and over, year after year, just with better graphics.

At the same time, I felt less and less interest in games' characters, worlds and topics, I felt bored seeing always the same stereotypes, poor storytelling and acting, gratuitous violence and total lack of any real meaning. I realized that most games were designed for an audience of kids between 10 and 14 years old. At 36, like many other gamers, I was definitely not a part of this target anymore.

Did it mean that I had to quit games like other players before me? Are video games just toys for kids and have absolutely no potential to become anything else?

This is how I decided to design Indigo Prophecy. I wanted to create a game that anyone could easily enjoy, that would not be based on the mastering of controls but on involvement. It would not rely on violence but on emotions, would not reduce interactivity to destruction but would try to show that it is possible to interact with something or someone without a gun. Last but not least, I wanted to create an experience for adults with mature, realistic, believable topics, not for 10-year-old kids. In short, I wanted to see if games had a chance to become more than toys one day.

I had absolutely no idea of the difficulty of this challenge, as I quickly realized that something was missing to create this experience: a language.

Interactive Storytelling, or the Holy Grail

Storytelling is one of the most ancient human activities. Every time mankind has invented a new form of media, it has used it to tell stories: spoken language, drawing, writing, theatre, cinema, and television. Why should videogames be the only exception?

Storytelling in videogames is usually very simple. We use stories in basically the same way as porn movies: a bit of story to set up the context and introduce the characters, then the big action scene. Another bit of story to set up the context for the next scene, then another big action scene. No one cares for the quality of the story, because no one is really there for that. The story is just a minor device wrapping action scenes.

My ambition with Indigo Prophecy was to create a game where storytelling would be at the center of the experience rather than a peripheral element. I strongly felt that it would allow me to extend the range of emotions that the game could offer. In my mind, a good story with interesting characters could convince anyone to want to play. Everybody wants to know what will happen next as long as they feel empathy for the characters. I thought I could transfer the challenge from "master the controller" to "make the right choices in the story and see how your decisions change the plot."

In most games, the story only progresses by means of cut scenes, as the action sequences generally carry no meaning. The main difficulty I knew I would have to face was to make the story progress through player's actions and not through cut scenes. The experience would have to be totally fluid and organic, and the story should progress naturally because of the player.

This main issue can be broken down into two smaller ones: interactive storytelling and interface.

Interactive storytelling is sometimes considered an impossible problem to solve: storytelling is supposed to be linear by essence while interactivity is non linear. The paradigm of interactive storytelling would be to let the player make choices that would have tangible consequences on the story. The simpler way to do that would be to offer choices as often as possible and manage all consequences. But choices would generate choices that would generate more choices, quickly resulting in a huge tree-structure that would be totally impossible to manage. Keeping track of all the choices and all their possible consequences in the story would create exponential possibilities.

On the other side, not having enough choices would result in a very linear story, a kind of Dragon's Lair experience where the player's choices would be limited to choosing A or B.

Last but not least, our experience would have to guarantee the quality and the pacing of the storytelling whatever the player does. No good or bad story depending on player's choices, but always a consistent and "dead-end free" experience. This is how I started working on what I call "Bending Stories". I think of my story as a rubber band; the player can stretch or deform the rubber band through his actions, but whatever he does the backbone of my story is always there. The player can have the feeling of playing with the story, almost in a physical sense by stretching it, but he can never break it. His choices can have very tangible consequences, but within the boundaries of a well-written narrative. Each scene, each action, can be considered like a rubber band itself, and each rubber band can stretch another rubber band later in the narrative, which can in turn impact the overall story. Possibilities are limitless and allow the writer to remain in control of the tale that is told.

This writing technique is similar to the "Choose your own adventure" books in a certain way; except that there are many more choices involved, and each choice can trigger consequences at any point in the story. Possibilities are truly endless.

I don't want to set wrong expectations: Indigo Prophecy and the rubber band story idea is not a proposition to generate dynamic storytelling. All events are scripted and the range of possibilities is pre-established, but this writing technique allows us to open a real narrative space within the story while maintaining its pacing and quality.

Consequences managed with this technique can be very significant for the player: in Indigo Prophecy, scenes can be played several times with different outcomes that may in turn affect other scenes. Two players playing the same scene can see or totally miss different parts of the game although both will experience the same overall story.

NEXT >>

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

INDIGO PROPHECY: Developer's Diary

- About Indigo Prophecy

- THE CONCEPT

- THE CONCEPT

- Some Thoughts About Games

- Interactive Storytelling, or the Holy Grail

- Interactive Storytelling, or the Holy Grail

- THE GAMEPLAY

- Game Design

- The Pen to Tell the Story: The Interface

- Game Mechanics

- Multiview

- Action Sequences

- The Pen to Tell the Story: The Interface

- THE STORY

- The Scenario

- Episodic Content

- Characters

- Episodic Content

- THE TECHNOLOGY

- Production

- Rendering

- Cameras

- IAM

- MOCAP

- Music

- Rendering

- CONCLUSION

My name is David Cage and I am the writer and director of Indigo Prophecy, and the CEO and founder of Quantic Dream. Before this game, I wrote and directed Omikron: The Nomad Soul, a game that featured famous singer David Bowie. My background is in the music industry although I have been a gamer since I was 10 years old.

I am 36 years old and have worked in this industry for the past 12 years. I founded Quantic Dream eight years ago to create innovative games, and to try to be among the pioneers discovering this new media.

When real-time 3D appeared, I immediately saw the incredible to create new kinds of immersive experiences. Since then, Quantic Dream has been entirely focused on creating original concepts, "emotional rides" blending narrative, cinema, music and interactivity.

About Indigo Prophecy

In this diary, I am going to tell you more about how we created Indigo Prophecy. People often ask me which category best defines this game and to be honest I have some difficulties answering that. The closest I can think of is probably the adventure genre, although Indigo Prophecy has no puzzles to speak of, nor does it require any inventory management. If I were to say that it's an interactive movie, you may think that it is the kind of game where you watch most of the time and press a button every hour, which Indigo Prophecy is not. Other people like to refer to it as a kind of 3D "create your own adventure book".

I like to call this game an "Interactive Drama", which in my mind suggests the fact that the player acts and interacts in a narrative and emotional experience.

The concept of the game is quite simple: put the player in the shoes of the hero of a movie and let him decide what he wants to do. His actions will have consequences that will modify the story.

For me, this game is unique in many ways: it aims to show that it is possible to create a game that is entirely story-driven without loosing interactivity. It also tries to create an emotional experience based on characters, relationships and moral choices, a game with a more adult tone.

Indigo Prophecy sounds like a simple concept, but taking it from paper to the shelves has been an interesting interactive adventure by itself... This is the story will share in this diary. I tried to cover all aspects of the development from concept to technology. I hope you will enjoy this quick overview of the last two years of my life.

NEXT >>

Labels: David Cage, Developers Diaries, English, Fahrenheit Indigo Prophecy

Previous News

- Detroit: Become Human

- Настоящий дефектив. Чем плоха расхваленная Heavy R...

- Beyond: Two Souls review: Beyond awful

- The Dark Sorcerer – a next gen comedy from Quantic...

- The Dark Sorcerer

- QD stories and projects not interesting anymore

- PlayFrance: interview David Cage

- [FJV 2009] Heavy Rain : Interview exclusive P3L de...

- Podcast: Kombo Breaker - Episode 45: Heavy Rain In...

- CVG: Heavy Rain delayed because it "needs space"

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

Tuesday, June 20, 2006